Why Analog Lost

Quantum Computing Probably Will Too

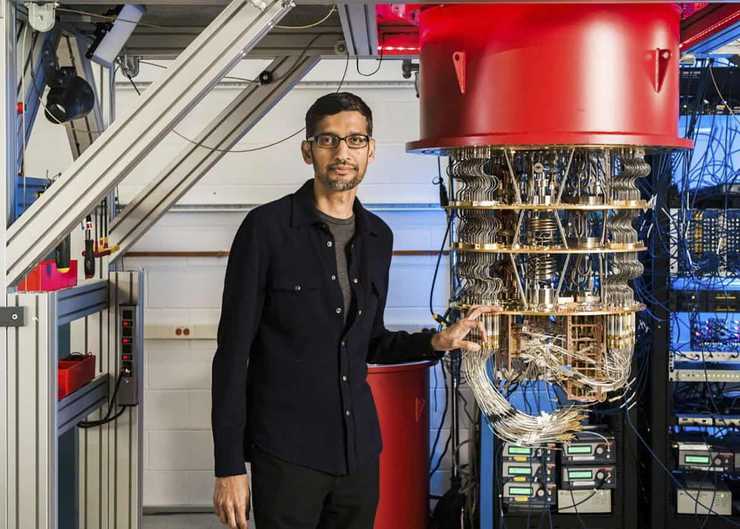

Sundar Pichai showing off Google's recent quantum leap forward. I don't think he buys it either.

I've spent most of my career building analog stuff - primarily the innards of silicon chips. For most of the past decade that was at Apple, where I designed the analog parts of overwhelmingly digital processors which serve as the brain of every iPhone, iPad, and Apple TV.

Point being, I have a whole lot of personal incentive for analog to, well, matter. The value of my personal skill-set is pretty well tied to the value of analog electronics in general. So it would be well within my self-interest to back a growing trend, and predict a coming analog renaissance.

But I won't.

I don't expect a comeback any time in the near future, or even any time in the distant future. Instead this article is about why analog lost in the first place, why that result is likely to stick, and whether any looming developments - particularly AI - have a chance to reverse it. We'll conclude with implications for the presumed next paradigm, quantum computing.

"Analog" Means "Offline" Now, But Not Here

We typically use the term analog in contrast with its common counterpart, digital. In the 2019 context, these terms often refer to differences between being offline and connected. We say that a taxi is analog, while an Uber is digital. A Blockbuster store is analog, while a YouTube stream is digital.

These uses are fine, and meaningful, but not what I'll be talking about here. This is about analog and digital electronics - the systems which underly the Uber request, the Netflix stream, and the entirety of our information-age lives.

Not long ago it was a real option, even a common reality, to use analog electronics in all sorts of places - including for computation. Over the course of the twentieth century, the analog and digital paradigms faced off. This was a fair fight; both combatants began staring head-on in the center of the ring. No referee was paid off. Neither side colluded with the Russians.

Digital won in a landslide.

Our world became digital, both in the colloquial, "connected" sense, and the engineering-level electronic sense. Every computer you use - now including between one and several dozen in every car, home appliance, and toy - operates on the digital paradigm. Analog was left relegated to the domains where it is the only available option - primarily those interacting with the physical world. It's Napoleon exiled to Elba, or Yoda on Dagoba. It hides in the limited confines where it can survive.

What is This Analog Stuff?

Analog systems' characteristic trait is that they represent information in continuous quantities. In typical realizations, including electronics, these continuous variables are mapped directly onto physical quantities: voltage, current, pressure, temperature, and the like. These direct analogies between information and its physical representation are the root of the term analog.

Digital systems, in contrast, represent information in, well, digits. (From which they also derive their name.) The overwhelmingly most common digital alphabet in electronics is binary, in which data are stored in quanta called binary digits or bits. Bits only have two values, which we often refer to as 0 and 1, or True and False.

There is a degree of freedom added in crafting a physical representation of a bit: a whole range of physical quantity can represent each digital value. In electronics, this is most commonly done by setting voltages "close to" one of two other widely-available voltages.

The Two Reasons

It's probably not yet clear why either of these things is inherently better than the other. In fairness, it's also mysterious (or just unconsidered) to most in the field. I see it as having boiled down to two factors.

- How We Think: Digital maps better onto our own thought processes and intuitions.

- Moore's Free Lunch: We found an implementation technology which made digital cheaper, and continued to rapidly improve.

Neither is a feature of the analog or digital paradigms per se. One is about history, and the other is about us.

Reason 1: How We Think

Design is a human endeavor; forget that and all is lost. -- Bjarne Stroustroup, creator of C++

This is not about why digital is better, but why it won. The digital-analog war was a sort of Darwinian contest, where fitness was decided by human choice. We found digital more amenable to use, and so continued to increasingly use it.

And this was for good reason. Our intuitions map particularly poorly onto the analog paradigm in a few areas:

- We hate uncertainty, noise, and anything that operates non-deterministically.

- We instead (strongly) prefer narrative, causal descriptions of how things work.

Causality

Crucially by "how we think", I do not mean how the mechanics of our brains work (neurons, synapses, and the like). I mean how we subjectively think, integrate information, and work through problems.

Take driving your car as an example. Most of us think of a drive as a sequence of steps:

- Go straight until you reach Mission St.

- Turn right. Watch out for hipsters on bikes and yuppies on scooters. Neither watch where they are going.

- After you pass three (unsuspiciously) recently-burned-down businesses, make another right.

These high-level directions form a set of what you might call "open-loop" instructions. There are no decisions being made, no internal feedback. A flow-chart would progress in a straight line.

But we also deploy this narrative tone more broadly, such as in lower-level, more feedback-sensitive, tasks. Imagine describing how you keep proper distance from a preceding car on the highway. Nearly everyone would say something like:

- If they speed up, I can speed up too.

- If they slow down, I have to slow down to keep my distance.

- If their brake lights turn on, they will probably slow down, very soon.

That if-then paradigm looks awfully digital. The analog paradigm, in contrast, would require a description more like:

- Accelerator foot-pressure equals an empirical proportion of the preceding car's velocity, or Fp = k * Vp

No one (except maybe the biggest nerds) would say anything like this. But the analog description is likely closer to the truth. Speeding up and slowing down don't happen in discrete events, but instead are taking place continuously, often subconsciously.

And even those (nerds) claiming to think in the analog paradigm would have a much tougher time with more than, say, four or five equations and variables. None of us have trouble making sense of a film with 4-5 interacting plot-lines, or even multi-tasking among 4-5 activities. But a spring-mass system with 4-5 interacting bodies proves intractable for almost everyone.

Noise

Perhaps the central difference between the analog and digital paradigms, and one where our intuitions divide most, is their handling of noise.

We use the term noise to represent a variety of phenomena largely unrelated in physical origin. Their common trait is the act of masking a desired signal. Some of these phenomena, which we'd more specifically call interference, are deterministic: if we only had access to more information, we could in principle measure and cancel them out. A nearby conversation drowning out your own is a common example. In electronics these interference phenomena are common due to electromagnetic coupling, for instance between nearby circuits or signals.

Other sources of noise are stochastic, or truly random. While we can make quantitative statements about stochastic processes in aggregate - i.e. their mean or standard deviation - by definition, they lack a mechanism for predicting their progression across time.

While both paradigms are subject to interference, digital symbols generally lack any sources of stochastic noise. Logic gates, flip-flops, and all other common digital-processing building blocks are, in this sense, noiseless. As long as the underlying physical representation of the bits play by the rules, their outputs are exactly correct, every time, forever.

Analog circuits, in contrast, generally include at least a few fundamentally stochastic noise sources, sadly paired with an inherent sensitivity to them. Since analog circuits represent information directly as physical quantities, any stochastic-noise injected into these physical quantities cannot be separated from desired signals. The digital paradigm adds a layer of indirection, trafficking in symbols which are represented by a range of a physical quantity. This has the happy effect of providing an essentially complete indifference to physics-level stochastic phenomena, and to many sources of interference.

Complexity

The digital paradigm wedges a layer of abstraction between information and its physical form. This is a lossy abstraction; plenty of detail disappears along the way. While this may seem to be a bug, it overwhelmingly turns out to be a feature.

I often analogize the chip and electronics design process to that of other complex systems: the Bay Bridge, SalesForce Tower, or the International Space Station. If we were designing these systems instead, and wanted to analyze or simulate them - what level of complexity would we use? Would, say, the molecular level seem appropriate? Of course not! We know these paradigms correctly describe the orbit of the ISS, far more accurately than we would ever care to know it. Their real problem is that they would take lifetimes to create and evaluate.

The level of detail we should use then becomes pretty obvious: the simplest one that works. What we mean by work is crucial here: more specifically, what will predict the behavior of the system, in the ways that we care about.

Digital has proven more powerful largely because it abstracts away a bunch of detail.

On "Black Magic"

A sad aside: analog practitioners (especially the RF variety) have developed an unfortunate practice of referring to themselves as being versed in black magic. The phrase is enshrined in the titles of books, web sites, and throughout a web's worth of information on the topic.

This is bullshit. Any scientific - really any fact-based - endeavor claiming to rely on black magic should not just be regarded skeptically, it should be presumed full of shit.

Practitioners of these "black" arts know that underlying their intuitions lies the same science dictating how everything else in the world works. There's no ghost in the machine, no supernatural explanation of success or failure. The phrase black magic has a simpler meaning: I don't understand this well enough to explain it to you.

Reason 2: Moore's Free Lunch

While the first reason boils down to a contingent fact about humanity, the second is ultimately a contingency of history. Right around the time we discovered the information theory to bounce back and forth between analog and digital paradigms, we also discovered an implementation technology which turbo-charged digital: CMOS semiconductor fabrication.

If Digital, Why Binary?

The importance of the underlying implementation-technology can perhaps best be shown through one question: why did all of our digital electronics turn out binary?

Digital information can, in principle, be stored in systems with any number of states. DNA and RNA, for example, use four-value encoding. At least one research group touts ternary (three-state) computing for high-performance and high-efficiency applications. These "multi-level" systems have similar logical algebras, analogous logic gates, and the capacity to generate just as wide an array of functionality. And we do really use them, at least in a few niche places. Popular wireline communication protocols such as PAM-3 and PAM-4 use three-level and four-level binary coding. Even more popular wireless communication schemes such as QAM similarly encode digital information in more than two states.

Yet the overwhelming majority of the digital world is binary. This includes every popular computer architecture and instruction set, and correspondingly every popular programming language. Any self-respecting computer language has a built in (binary) Boolean type. None (to my knowledge) include a three, four, or more-state such primitive.

So why did digital electronics near-universally settle for binary? Wouldn't allowing every signal to have, say, four states be "twice" as efficient in some sense than only two? For that matter, wouldn't eight, or 23, or 317 such levels be even more powerful?

In principle, they might. But only binary logic was powered forward by a freight-train of underling implication technology. Even before decades of generation-on-generation advances, the combination of integrated-circuit fabrication and CMOS logic was already an awfully good deal. CMOS uses a combination of two (C)omplementary flavors of MOS (metal-oxide-semiconductor) transistor to represent binary signals as voltages "near" one of two widely distributed power-supply voltages. This leads to logic circuits which are highly compact, robust, and power efficient. The CMOS style powers essentially every digital chip you use. (And depending on you age, potentially all that you have ever used.) The two workhorse universal gates of the boolean algebra, NAND and NOR, each require only four transistors. Simple memory cells require only six.

Analog circuits also play nice in CMOS technology. Advances characterized by Moore's "free lunch" also improve analog circuits, just by less than they have typically improved digital circuits.

####Make No Law

No matter how powerful a force semiconductor fabrication has been, the phrase Moore's Law has always been off. The inclusion of the term law, coupled with the fact that it concerns a complicated scientific-seeming topic, leads people to believe it is some law of nature, like Newton's laws of motion or the second law of thermodynamics. Or perhaps more like Ahmdal's law, which sets a theoretical limit on a category of abstract quantities (computer programs).

What Gordon Moore made, in truth, was a prediction about people. Particularly the intellectual progress of a group of people driving semiconductor fabrication. He predicted an exponential rate of progress in this field, extending indefinitely into the future. Countless inventions and person-years of their work caused this prediction to hold over decades.

For most, the notion of an end of Moore's Law also fails to dispel this notion. No one expects gravity or entropy to end, much less any time soon. But many accept chip-progress as a fact of nature, somehow limited to the late 20th century.

Perception of Moore's Law is sort of like Gordon Moore had arrived in Chicago in the early 1990s and declared, this Michael Jordan guy is so good, his team will win the championship every year - and the society-wide reaction was a complete internalization of this expectation. So complete that we all ceased to notice it as an achievement. This Moore's Jordan's Law would then only enter our consciousness to disappoint us when violated, whether due to circumstances on the court or Jordan's eventual retirement. Why shouldn't a Jordan team win every year? It's a verified law of nature!

Nature is Analog, and Digital

Analog enthusiasts tend to note that analog cannot go away, because nature is fundamentally analog. There are a few problems with this idea. First, going away - disappearing altogether - is an awfully low bar. Inventions far older and less useful than analog electronics have avoided such extinction. Horses-drawn carriages and muskets still exist, despite centuries of superior replacements. They just serve tiny and continually shrinking niches.

More important: nature is analog, except when it isn't. Temperature, air pressure, frequency, time, and a whole slew of natural phenomena we experience are (as best we can perceive) analog. Many others are digital. Most species have a digital number of sexes, arms, legs, eyes, ears, and lungs. Perhaps the most impactful such digital phenomena lies in genetics. Humans and essentially every other species encode their inter-generational traits in digital form. DNA is encoded in a four-value alphabet represented by the four protein units adenine, cytosine, thymine, and guanine, commonly referred to as A, C, T, and G.

Analog's Latest Champion

("Champion" in the same sense as these guys, despite one getting his head crushed and the other becoming a zombie.)

Prospects of an "analog renaissance" have been promoted by many, perhaps none more prominent than historian George Dyson. Dyson's work spans the modern history of computing, science, and technology, and prospects for its future. You can him find speaking at TED, discussing artificial intelligence in books, on Edge.org, or on popular podcasts. He is also the son of quantum electrodynamics pioneer Freeman Dyson.

While Mr. Dyson clearly believes that the future of computing is analog, he has a bit rarer take on the current state of affairs. He writes that this revolution is not only in our imminent future, but has already been happening all around us, practically right under our noses. More than once Mr. Dyson has keynote-spoken on how we have gone from analog to digital, and back. From a recent Edge.org conversation and podcast:

If you look at the most interesting computation being done on the Internet, most of it now is analog computing, analog in the sense of computing with continuous functions rather than discrete strings of code. The meaning is not in the sequence of bits; the meaning is just relative. Von Neumann very clearly said that relative frequency was how the brain does its computing. It's pulse frequency coded, not digitally coded. There is no digital code.

At first glance, that's pretty tough to buy. All of the computing I know (save for the research lab) gets done on computers that are awfully digital, and use, well, strings of code. Maybe Mr. Dyson has a very different view of what computations are "most interesting". He elaborated on this in an essay:

Analog computing, once believed to be as extinct as the differential analyzer, has returned. Not for performing arithmetic — a task at which even a pocket calculator outperforms an analog computer — but for problems at which analog computing can do a better job not only of computing the answer, but of asking the questions and communicating the results. Who is friends with whom? For a small high school, you could construct a database to keep track of this, and update it every night to keep track of changes to the lists. If you want to answer this question, updated in real time, for 500 million people, your only hope is to build an analog computer. Sure, you may use digital components, but at a certain point the analog computing being performed by the system far exceeds the complexity of the digital code with which it is built. That's the genius that powers Facebook and its ilk. Your model of the social graph becomes the social graph, and updates itself.

In the age of all things digital, "Web 2.0" is our code word for the analog increasingly supervening upon the digital — reversing how digital logic was embedded in analog components, sixty years ago. The fastest-growing computers of 2010 — search engines and social networks — are analog computers in a big, new, and important way. Instead of meaningful information being encoded as unambiguous (and fault-intolerant) digital sequences referenced by precise numerical addressing, meaningful information is increasingly being encoded (and operated upon) as continuous (and noise-tolerant) variables such as frequencies (of connection or occurrence) and the topology of what connects where, with location being increasingly defined by fault-tolerant template rather than by unforgiving numerical address.

That's definitely a lot of stuff. Maybe some of it even sounds cool.

But it's hard to find even a kernel of truth. Case in point:

Who is friends with whom? For a small high school, you could construct a database to keep track of this, and update it every night to keep track of changes to the lists. If you want to answer this question, updated in real time, for 500 million people, your only hope is to build an analog computer.

"Constructing a database to keep track of this" is exactly what Facebook does, nowadays for several billion users. And all of the computers and databases involved are quite digital.

Even old-fashioned-analog concepts such as "friendship" are turned digital in such systems. Facebook-friendship is not only digital, it's binary. You can be friends with another user, or not. There are two available states; there is no middle ground. You cannot be friends of level 13 versus level 99, much less level 3.14159.

Real life, in this sense, is analog. Each of your friends come at different levels of breadth and depth, potentially differing by topic and situation. You might be great friends in a poker game, but complete strangers regarding your professions or romantic relationships. Even if Facebook attempted to extract a multi-level measure of "friend-ness", perhaps using shared friends, conversations, or photos, Facebook would still store these quantities very digitally. And if Facebook decided to add this "friend-ness" to a neural network, it would be digital too.

After the AI Takes Over

Notions of an ongoing analog renaissance are misguided at best. But more credibly Dyson, and many more analog-advocates, often make a separate (strangely co-located) argument about a future analog renaissance led not by humans, but by AI. From another Edge.org essay:

Machines that actually think for themselves, as opposed to simply doing ever-more-clever things, are more likely to be analog than digital, although they may be analog devices running as higher-level processes on a substrate of digital components, the same way digital computers were invoked as processes running on analog components, the first time around.

Setting aside the category-errors of this "substrate" argument, the case for analog AI seems plausible. If (more likely, when) advances in artificial intelligence render humans irrelevant in the design of future systems, human intuition will no longer be terribly relevant to what technologies our AI-overlords decide to develop. (Although strangely Dyson simultaneously argues that the analog renaissance is already underway. Maybe the AI revolution also snuck up under our noses.)

There is no particular reason to expect super-human - perhaps many orders of magnitude greater than human - intelligence to share our intuitions, tendencies, or biases. The biases away from uncertainty and noise, towards narrative and causality have undoubtedly extracted a tax on the quality of human-designed systems. A perfectly rational AI could in principle shed them and be left with a more pristine set of criteria for what works best. It then stands to reason that the future may in fact be analog. Future AI could generate a return to analog systems, which in principle offer a few powerful points of flexibility which digital systems cannot.

But it's also possible, and just as likely, that AI-designed systems would be quantum, or digital, or any other mix of any number of paradigms. That AI would not share our cognitive preference for digital does not mean that it would hold a counterbalancing preference for analog. Analog and digital are not opposites, nor are they the only ways of storing and processing information. Quantum computing provides an immediately available counterexample.

But future AI may also venture further afield. Our information age has been built on primarily electronic media. Virtually all computers, storage, and communication uses electronic means. Information is, by and large, represented by the location of handfuls of electrons. While sound and light have always been valuable communications media for humans, they are rare in communication between machines. High-performance optical-fiber links are an exception; these comprise a far smaller share of machine-machine communication than audio and video comprise human-targeted communication.

Will our future AI overlords retain our affinity for storing and transmitting information with electrons? Maybe. But just as they need not retain our affinity for the digital paradigm, there is no assurance that artificial designers will prefer electronics at all. They seem just as likely to find means of storing information which we have not conceived. Perhaps using temperature, air pressure, or gravity. Instead of electrons, data might be conveyed with gravitons, photons, Higgs bosons, or any number of as-yet undiscovered physical phenomena.

There is perhaps one factor making it more likely for AI to prefer digital systems. At our current technological state and pace of development, it appears increasingly likely that the first super-human intelligences will be made of digital electronics. Perhaps the very constitution of AI will cause it to favor the digital paradigm, at least for a time.

Outlook: Quantum Computing

Here we've argued that digital beat analog for two not-super-intuitive reasons:

- (1) The digital paradigm maps better onto how we think, and

- (2) We found a powerful and improving implementation technology on which to build digital logic.

If true, that bodes particularly poorly for one emerging technology: quantum computing.

We have rarely seen a technology more poorly suited to human intuition and efficient implementation than quantum computers. The pitch for quantum computing generally starts with an intro to "quantum bits", or qubits: think of bits, but which instead of storing one of only two values, they can store an infinite number! Our review of the digital-analog divide should render this pretty unspectacular. We've always had "analog bits", usually called analog signals, with an infinite number of possible values.

Computations generally rely on the quantum phenomena of entanglement between qubits, or quantum states of particles. Performing an elaborate computation generally requires entangling a set of qubits in a particular configuration and observing one. Poof! All of the rest resolve too.

It would be hard to find a mechanism of computation less amenable to human intuition that quantum entanglement. This was the exact facet of quantum mechanics that Albert Einstein famously derided as "spooky action at a distance". In truth we still don't really understand how or why it works.

Entangling qubits has also proved to be at a painful intersection of two more traits we've reviewed: implementation technology and noise sensitivity. Existing quantum computers require a high-end science-lab-grade implementation technology, generally requiring temperatures near absolute zero. Entangling qubits is both the important part and, well, the hard part. Noise levels in existing quantum computers make analog computation look high-precision by comparison. IBM's advice when running quantum computation is to repeat each one, generally dozens of times. (In other words, oversampling.)

To be fair, quantum computing offers promises that analog never could. If only we could entangle, say, 100 qubits, the work inherent in each computation would be something like 2^100 times a typical digital-computer operation; we would have plenty of time to over-sample and still come out ahead. Unfortunately such levels remain on the distant horizon.

As a twenty year old student of physics and engineering, I was convinced that my life's work would be towards ushering out the digital era, and ushering in its quantum replacement. Fifteen years later, I expect that quantum computing won't amount to shit, at least in our lifetime. (By "shit", I mean a material economic or popular impact, outside of a research setting.)

Maybe after our AI overlords take control.

While this chapter has been a little different, Software Makes Hardware is (usually) a dive into how silicon and electronics get designed, for the software-engineering inclined. (It turns out we're not so different after all.)